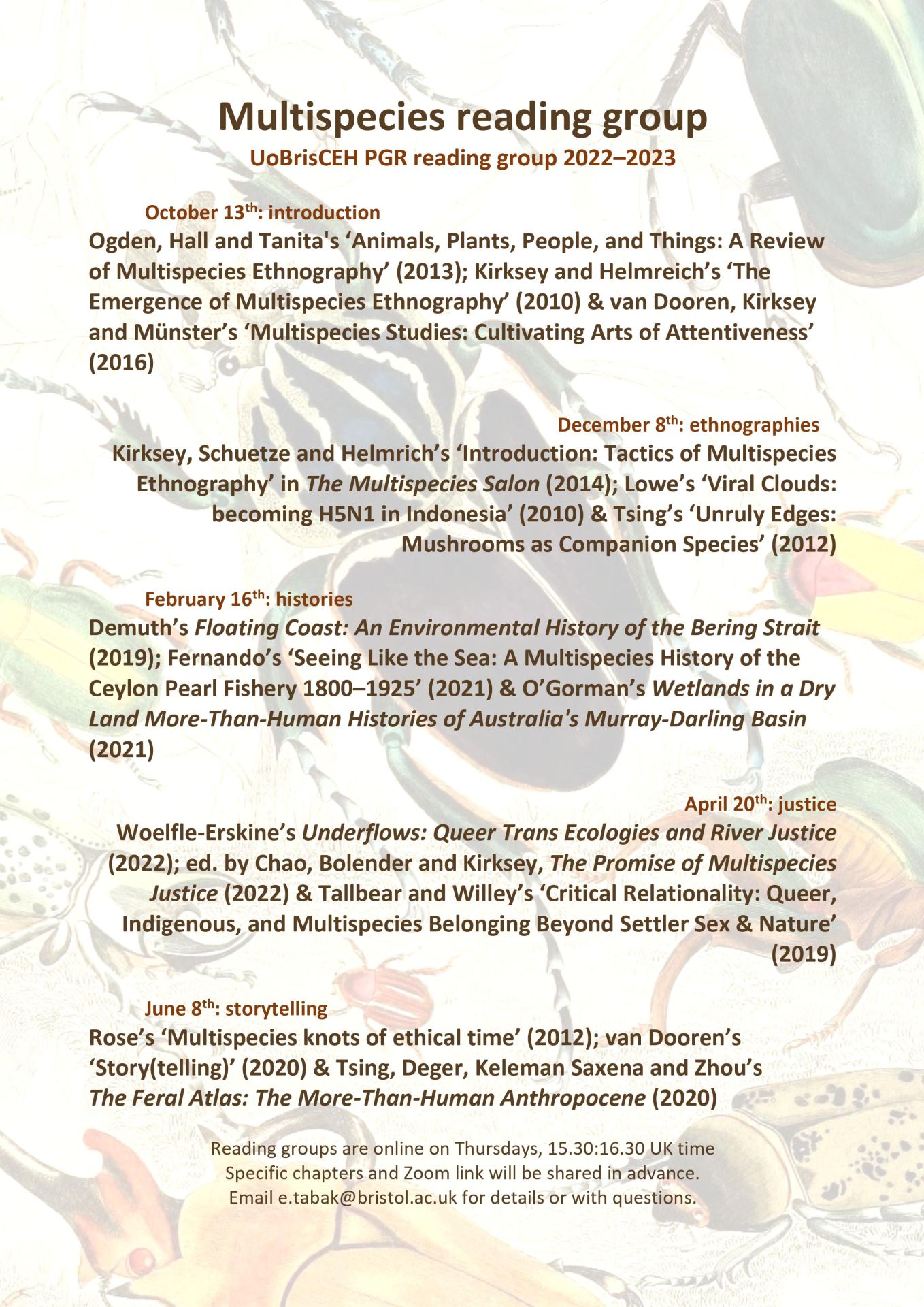

This post is reblogged from Milo Newman‘s blog, Mourning Auks: exploring creative articulations of ecological loss. Milo is a third-year PhD student in the School of Geographical Sciences.

The post details a period of artwork production and fieldwork on the island of Papay in Orkney, forming part of a PhD project exploring bird extinction through creative practice.

Time passes, washing over the island in a cycle of near continuous day. The Earth spins, and the sun is drawn down into a brief dusk, pulling light into the sea and lower sky. My plaster eggs, held in their pinhole cameras, collect all this illuminance onto their surfaces. Occasionally the haar drifts in, a sea fog borne by the wind. Moisture condensed over the coldness of the North Sea clags over the island. Distance collapses to a world of immediacy, to sequences of greys and eerie silhouettes. The experience of this light also gathers onto the eggshells.

On mornings when the haar is absent and the Holm is visible I often walk down to the beach and scan its distant shore with my binoculars, counting the pinhole cameras, and checking if they still look secure. Over the course of these repeated inspections I realise that the eggs are perhaps not recording a period of former care as I had imagined. Rather, they are collecting a durational space—one of reflection, or meditation perhaps, on the collapse of avian becoming (Rose, 2012; Rose et al., 2017; van Dooren, 2014) that is quite visibly occurring here.

As the most perceptible sign of this dull slide towards extinction (again see van Dooren, 2014), it’s been impossible not to keep thinking about the H5N1 influenza virus. Though just one of many pressures impacting the seabirds here and driving their decline, it is by far the most noticeable. The morbidity is devastating. Even though I am here researching such exterminating processes there are days when I find it too overwhelming—when I can’t bear to see any more sick, dead, and dying birds. Avian lives are precarious at the best of times, but the far-reaching ripples of anthropogenic activity, (including H5N1, which emerged in the virus laboratory that is industrial-scale poultry farming) mean that recovery from such mass mortality becomes harder and harder.

The forty-four day photographic exposure I’m recording to mimic the incubation of the extinct auks has been marked by this experience of death. On my walks I see the corpses of birds everywhere. Gannets protrude from the sand, half buried. Sometimes just the tops of their heads protrude, the feathers moving slightly as the wind scrapes the ground, rippling the beach away into streams of matter. Still other birds lie discarded amongst the seaweed on the tideline; guillemots, fulmars. Tattered feathers are strewn throughout. On another day I am invited to come and collect the dead bonxies (great skuas) that litter North Hill. There is a concern that this might spread disease by transferring the virus around on boots and clothes, and also a deeper anxiety that contact (albeit brief) risks giving the virus the opportunity to mutate and jump species. However, these apprehensions are countered by the fact that doing nothing also risks allowing the virus to spread. By leaving deceased birds to decay they are often scavenged, and can contaminate bodies of water. We use litter pickers to collect the carcases, lifting them around their necks and dumping them into binbags. It is depressing work. Many look to have died in anguish; their wings contorted and their heads pushed hard into the soft ground. Over the course of the afternoon we gather the bodies of a third of Papay’s breeding population.

I find myself thinking through the space of the island, and how it has been changed by all this death. Or rather, not how it has changed, but what falsities have been revealed in how space is predominantly conceptualised. I remember whilst gathering the dead bonxies looking up and catching sight of the trig point beneath the clouds on the summit of North Hill. Providing a fixed position from which triangulation can occur, these pillars allow land to be abstracted into grids, and accurately mapped. But to be amidst this unravelling ecosystem is to feel unmoored from the certainties such spatial imaginings promise. The island is not a space of fixity, but one of flux. Its moods change with the weather fronts that pass so rapidly overhead. Further, its small size does not equate to simplicity—it is a locus of complexity, where drifts of matter and lives snag and are held for various lengths of time. Deeply entangled ecologies bloom over evolutionary time. Their being, again, is not fixed, but fluctuates and transforms. Worlds are co-shaped; ways of being are re-negotiated in every moment between organisms themselves, and with a world that changes around them. The character of space gathers, coheres, and transforms through relations.

The idea of the island as a place with fixed boundaries also begins to break down. On a simple level, its erosion is an ongoing process. The coastlines change shape almost daily; the sandy eastern shore especially so. But the island also reveals a deeper porosity. This is perhaps made most visible through the H5N1 virus itself. Celia Lowe (2010) writes how viruses, rather than existing as well-bounded organisms are quasi-species that form and enact their identities with others. The virus blurs the boundaries between bodies, between species. As she puts it, multiple ways of being are:

‘transformed amid encounters among viruses[:] the immune systems of animal hosts, and the human institutions that struggle to reckon with the specter of a terrifying pandemic. One can think, then, of [the space of the virus as] “multispecies clouds,” collections of species transforming together in both ordinary and surprising ways.’ (Ibid., 626)

I find I have begun to draw imaginative connections between these viral clouds, and the haar that at times glides in and envelops the island. The viral cloud is transformational. It affects and alters my being, even if infection is avoided. Indeed, it is impossible not to be pulled apart emotionally whilst witnessing the individual suffering of so many birds.

The melancholy fact is that we exist in a world of change, and live long enough to notice long-term declines. We might remember the abundance of the past and compare that memory to how things are now, and wish to return. I often fear this is an impossibility. We might also find solace in the promise of deep, evolutionary futures; with the prospect that at some point life’s richness will repair itself. But, this argument disavows the beauty that still surrounds us amidst these unravelling worlds, and leads towards the easy options of acceptance and inaction. Just as the haar collapses distances, the viral cloud holds us in the present, and in proximity with intense vulnerability.

Some days it feels like enough research just to walk out amidst the blurred, rain-filled light onto the hill and watch the remaining skuas wheeling over the darkened ground of their territories, white flashing from their wings. As I sit in the midst of such relation, I feel that we should not quietly accept the injustices that ripple into this shared realm.

References

LOWE, C. 2010. VIRAL CLOUDS: Becoming H5N1 in Indonesia. Cultural Anthropology, 25, 625-649.

ROSE, D. B. 2012. Multispecies Knots of Ethical Time. Environmental Philosophy, 9, 127-140.

ROSE, D. B., VAN DOOREN, T. & CHRULEW, M. 2017. Introduction: Telling Extinction Stories. In: DEBORAH BIRD ROSE, T. V. D. A. M. C. (ed.) Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations. New York: Columbia University Press.

VAN DOOREN, T. 2014. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction, New York, Columbia University Press.

Read the original post on Milo’s website.