A post by Dr Pippa Marland (University of Bristol Department of English, and Centre for Environmental Humanities)

This time last year, in my role as one of the Land Lines team at the University of Leeds, I helped to organise a crowd-sourced online Spring nature diary, in collaboration with the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the National Trust. Taking place on and in the week following the 2020 Spring Equinox, the event coincided with the UK entering its first period of lockdown. As people uploaded their written and visual snapshots it became apparent that not only were we seeing a picture of spring arriving across the country, but also witnessing the cumulative record of what nature meant to people at a time of personal, national and global crisis.

In April 2020 this dimension of the diary was reported in The Guardian in an article that highlighted the way in which the entries spoke of the solace and hope nature offered at this time. The piece also referred to the breadth of the public response to the event and, in fact, the diary had been envisioned as contributing to a democratisation of nature writing through welcoming a range of new perspectives to a genre that throughout its history has been something of a monoculture.

As a result of the Guardian coverage, Rupert Lancaster, Non-fiction Publisher at Hodder and Stoughton, got in touch with me to suggest a collaboration. He was keen to develop the idea of a seasonal almanac, and we immediately contacted Anita Roy, author of A Year in Kingcombe, which traces the course of year in a Dorset nature reserve, to see if she would be interesting in co-editing the book with me. From the start, we wanted to curate a series of essays by diverse, distinctive voices – brilliant authors who might not be immediately associated with the nature writing genre, but whose work nevertheless often revolves around the subject of nature. We also wanted to commission essays that represented a kind of dialogue – with the British landscape, with people’s individual and collective cultural histories, with ideas of ethnicity, disability, sexuality, gender and class, and with existing literary traditions of writing about the natural world.

Anita and I drew up a wish list, hoping to mix emerging authors with some well-established names. Nearly all of them said yes. From early on we had the support of the Poet Laureate, Simon Armitage, who allowed us to take a passage from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for our epilogue, and it was while discussing Simon’s contribution to the project that Rupert suggested as a title for the collection the phrase ‘gifts of gravity and light’ from Simon’s poem ‘You’re Beautiful’. We’d been mulling over numerous different possibilities, but this one resonated very powerfully with us. It symbolised the kind of balance we were looking for – between the weight and darkness of writing about nature in the midst of the Anthropocene and the inspiration and illumination that can still be involved in exploring the natural world and our place in it.

We were delighted when Bernardine Evaristo, a tireless champion of diversity in all genres of writing and winner of the 2019 Booker Prize, agreed to write the foreword for the book. Jackie Kay, the outgoing Scottish Makar, also gave us her gracious permission to reprint her New Year poem ‘Promises’ as the epigraph. As the collection progressed, Anita and I assessed our own role as editors and realised that we didn’t want to write a standard introduction to the volume. Instead we decided to contribute our own pieces of creative writing – equinoctial ‘hinges’ for the spring and autumn sections of the book.

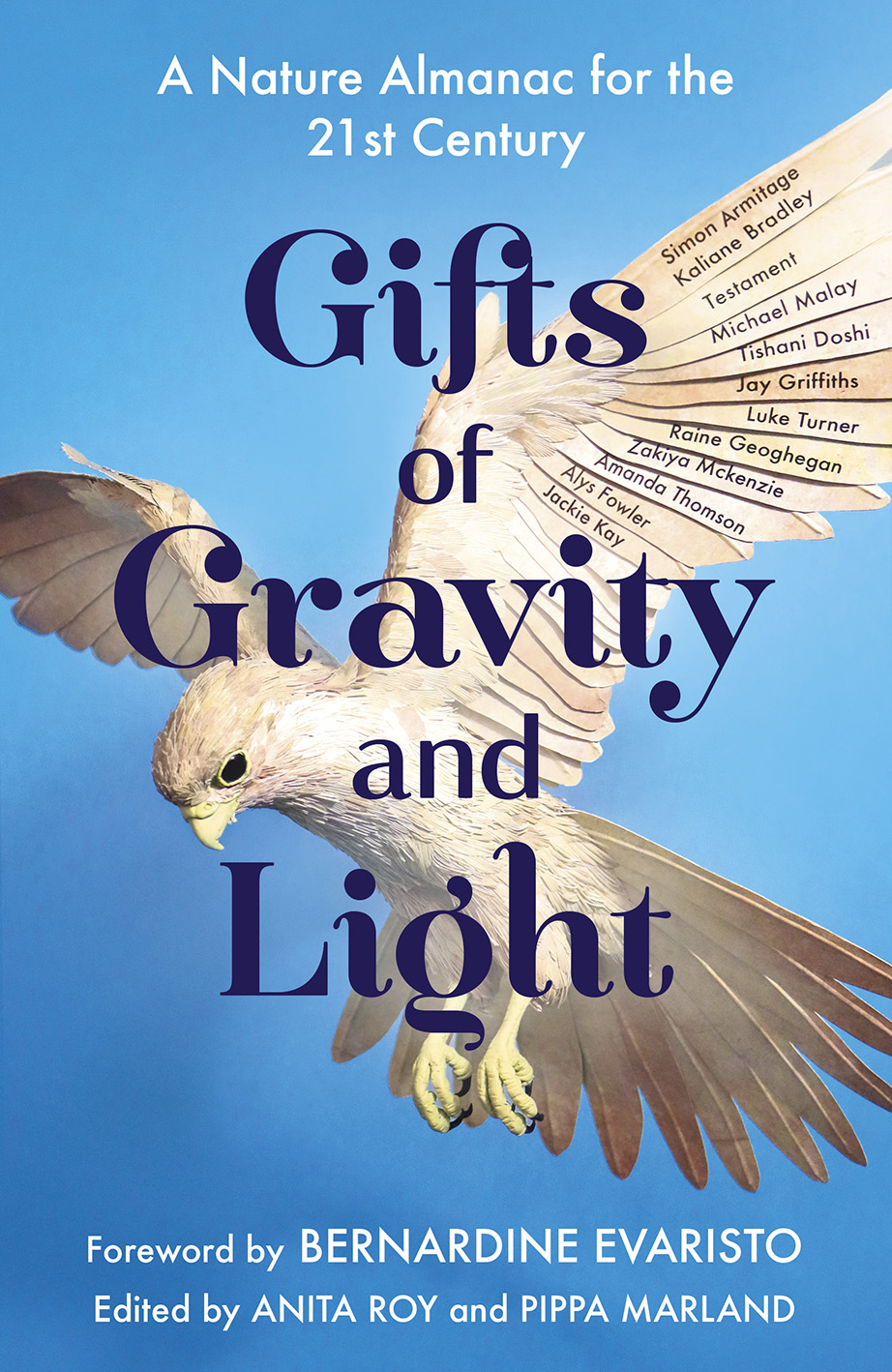

Now, a year on, we are checking the proofs and today we’re revealing the beautiful cover, which features a kestrel, or windhover, made by the artist Zack Mclaughlin. It has the names of the contributors – Kaliane Bradley, Testament, Michael Malay, Tishani Doshi, Jay Griffiths, Luke Turner, Raine Geoghegan, Zakiya McKenzie, Alys Fowler, and Amanda Thomson – all fanned out on the bird’s lifted wing.

Michael Malay is, like me, a member of the Centre for Environmental Humanities at Bristol, and is rapidly gaining recognition for his nature writing, being shortlisted for the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize in 2019.

The book’s content reflects not only the diversity of the authors’ voices but the endlessly changing natural world itself. There are meditations on mud – in a Birmingham park and in the trenches of the First World War – on greeting the arrival of cherry blossom in East London with a Cambodian New Year’s dance; on seeing nature pushing through the cracks of a Manchester pavement; on watching sea otters at play in the summer sun; on imagining eels gathering in the dark waters of the Bristol Channel; on leaving India to spend summers in Wales; on hearing Romany family stories of celebrating the hop harvest; on experiencing the icy stillness of winter in the Cairngorms or remembering the ‘sun drunk’ days of a Jamaican childhood in the chill of a British Christmas.

For me, working on this collection has been an absolute gift of light in a dark year, as has collaborating with Anita Roy and the team at Hodder and Stoughton. Gifts of Gravity and Light will be published on 9th July 2021 and is available for pre-order from Waterstones, Bookshop.org and Amazon, among other outlets.

![[image] Jackson - On decolonising the Anthropocene blog post](https://environmentalhumanities.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2020/07/image-jackson-on-decolonising-the-anthropocene-blog-post.jpg)