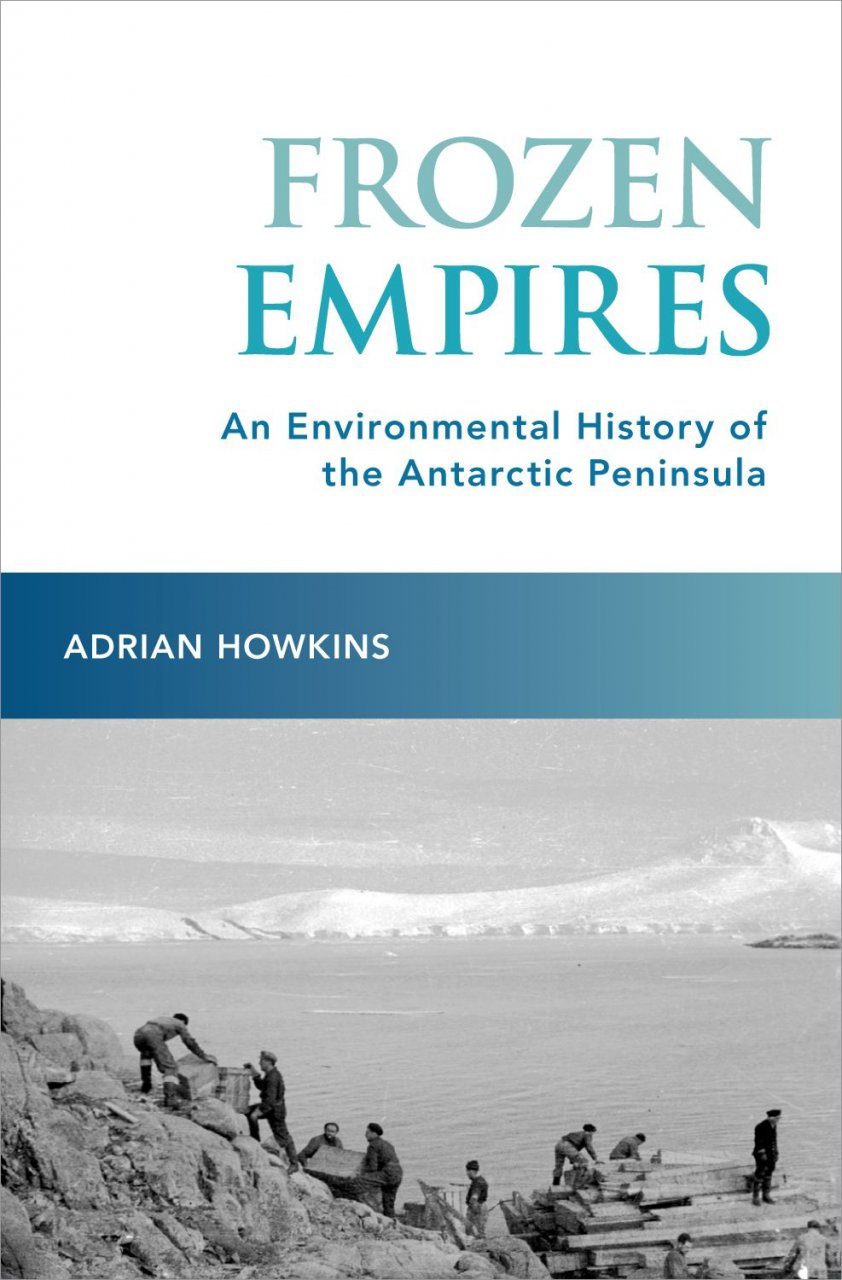

In this blog post, Dr Adrian Howkins, programme director of the new MA Environmental Humanities, discusses how his research on Antarctica brings crucial humanities perspectives to Antarctic research, and how this approach is embedded in the new MA programme.

Since the late-1950s the McMurdo Dry Valleys have become a major centre for Antarctic science. As an environmental historian, I have been able to contribute novel forms of ‘data’ to the scientific understanding of the region, such as using Captain Scott’s diaries to understand environmental change over the past 120 years. As a historian, I am also well-placed to ask questions related to themes such as political power, social relations, ideas about conservation, and connections to global themes.

I am currently working with a geographer and a glaciologist to write a co-authored book on the history of the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Some of our major findings support the fact that a human and historical dimension to conservation is vital. These include:

- The science taking place in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is used by national programmes to support their political interests in Antarctica. The US flag, for example, flies proudly from the Lake Hoare scientific field camp, offering a powerful refutation of New Zealand sovereignty claims to the region. This means that successful conservation needs to take into account the geopolitical implications of environmental management.

- The past 30-years have seen an increase in gender equality among scientists working in the McMurdo Dry Valley. Female scientists who may previously have been put off research in the region by its highly masculine culture, now make major contributions to the scientific work. The number of scientific publications on the region has increased significantly during the recent period, suggesting that greater gender equality may help to promote a productive scientific culture.

- Traditional approaches to environmental management don’t always take humanities-focused values into account. For example, the value of ‘wilderness’ is often taken for granted, while our work shows that some countries working in the region (e.g. Japan) do not always share these values. By raising questions about the goals of conservation and the cultural values behind them, our work calls for more focus on the human dimensions of Antarctic conservation.

- Our work in the McMurdo Dry Valleys exemplify many of the themes and trends associated with the proposed new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene. Work in the region is made possible by carbon intensive technologies such as helicopters and ATVs, while at the same time, scientific work in the region highlights the consequences of anthropogenic climate heating. Lake levels in the region, for example, have risen by over 16m since the time of Captain Scott as a consequence of more meltwater flowing from the alpine glaciers during the relatively warm summer months.

- Through our historical research in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, we not only hope to make a contribution to the scientific understanding, but also to make the region a model for interdisciplinary research involving the environmental humanities in other parts of the world.

Our work suggests that many of the challenges facing the McMurdo Dry Valleys – and the Antarctic continent more generally, and even the rest of the world – cannot be successfully addressed without taking into account perspectives traditionally studied by humanities scholarship. Such work requires a willingness to take a collaborative approach and be open to different approaches and practical skills. As authors, we hope to model this ‘radical interdisciplinarity’ not only in our book on the history of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, but also in our teaching. The new MA in environmental humanities at the University of Bristol, for example, has a strong element of collaborative and interdisciplinary training and is underpinned by activities in Bristol’s Centre for Environmental Humanities.

Find out more about MA Environmental Humanities at Bristol

Dr Adrian Howkins is Reader in Environmental History at the University of Bristol.

Dr Adrian Howkins is Reader in Environmental History at the University of Bristol.