Josepha Richards’ postdoctoral research explores the archives of an 18thcentury British botanist – John Bradby Blake – whose personal project was to make Chinese plants better known in Britain and its colonies. She explains this early attempt to compile a Chinese “flora”, how he relied on the help of Chinese to gather information and what were the wider consequences of his work (notably on the environment of British American colonies).

In the 1770s, the English trader John Bradby Blake made one of the earliest systematic attempts to document the diversity of Chinese plants, based on careful observations of the material he was able to access while based in China. His time there coincided with the operation of the Canton System (1757-1842), when Guangzhou (Canton), along with nearby Macao, was the only harbour open to Westernerswanting to trade with China.

John Bradby Blake appears to have been a self-taught botanist prior to becoming a trader with the British East India Company in 1766. He put this expertise to work shortly after he began his duties in Guangzhou as ‘supercargo’. From the start, Blake’s goal was to use his spare time in the off-trade season to collect the plants that he encountered, many of which were little known in Europe at that time. Before embarking for China, Blake had met with eminent naturalists such as Daniel Solander and John Ellis in London, who advised on using the recently created Linnaean system to classify previously unknown Chinese plants.

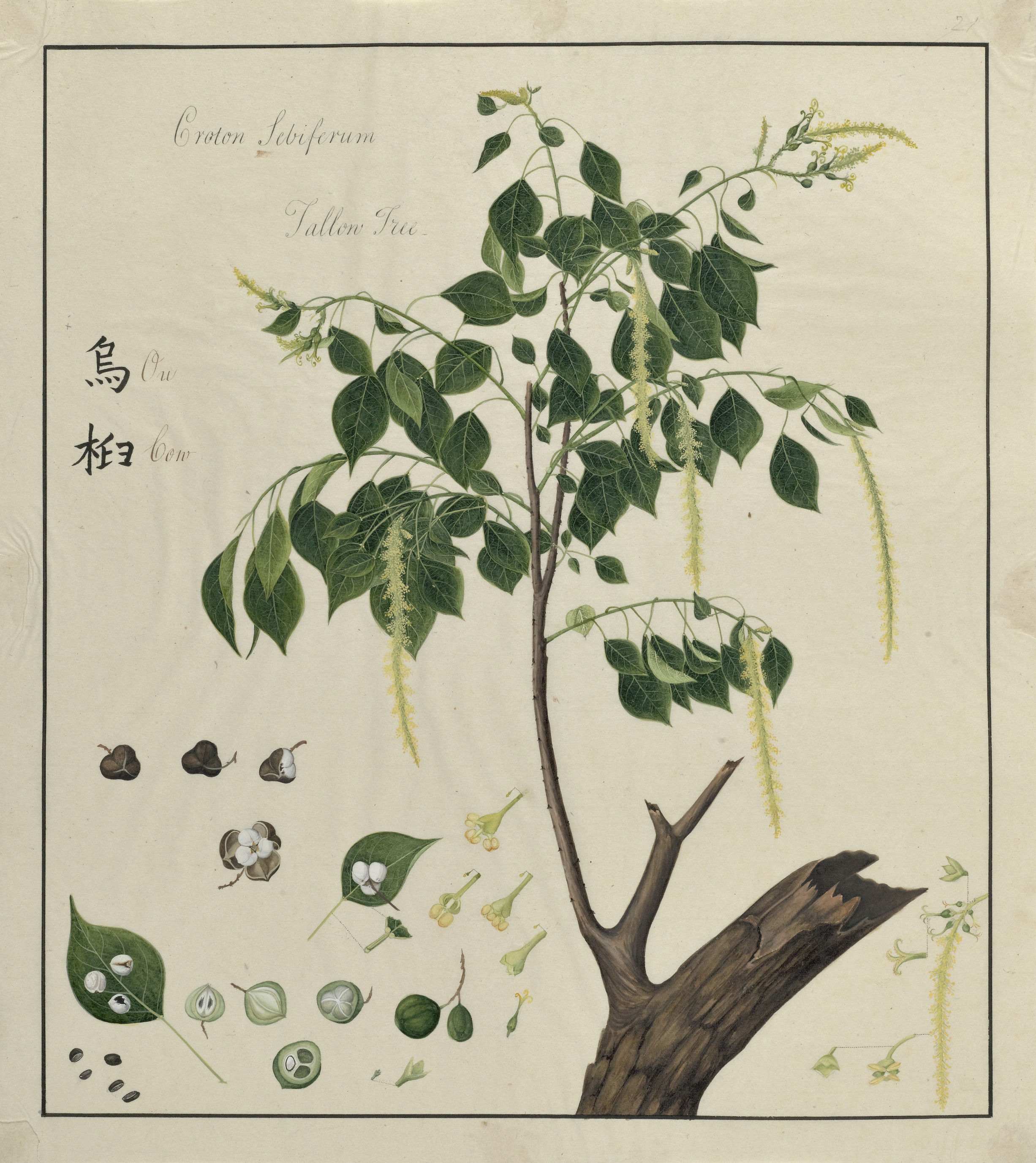

Around 1771, Blake started to produce drawings and notes for his Chinese “flora”. He chose the plants he wished to include based on the material to which he had access in Guangzhou, and by comparing those plants with others described in several Western botanical books that he had brought with him. Much information also came from the translation of Chinese botanical books such as the classic Chinese book of medicinal plants, the Bencao Gangmu(Compendium of Materia Medica). Whenever he could, he also obtained seeds of certain plants of particular interest and planted them, following advice from local Chinese garden owners and gardeners. Blake also commissioned and worked closely with a Chinese artist named Mak Sau to produce realistic, scientifically accurate, drawings of the plants, often including different stages of their growth, for example both flowers and fruits.

Blake regularly sent seeds to England to his father, a retired East India Company ship’s captain. Blake senior then distributed the seeds to recipients across Britain: not only to major institutions, such as the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew, but also to commercial plant nurseries in London. Among those who received seeds were also several correspondents in the developing British American colonies.[i]The plants that Blake was interested in were diverse, and included several ornamentals such as the sought-after Camellia, but Blake seems to have been especially focused on plants with practical uses such as Chinese medicinal plants, or plants with economic uses (dye, food crops, wax).

The British American and Caribbean colonies were particularly eager for any new economic crops. It is no surprise then that the plant which among all of Blake’s findings had the widest environmental impact, was one sent to the American South and Caribbean: the Chinese tallow tree (Triadica sebifera sebiferaL.), used by the Chinese to produce a form of vegetable wax. Not only did Blake take lengthy notes on how the Chinese grew the plant and processed it in order to produce wax; but he also commissioned a series of detailed paintings and sent them with seeds, via London, all the way to South Carolina, Georgia, and the St. Johns River in Florida in the American colonies, as well as St. Vincent in the Caribbean. The tallow tree did very well in the American colonies, and Blake is therefore indirectly responsible for encouraging further exploration of its use in the 19thcentury. Unfortunately, the species turned out to be pernicious invasive with negative environmental impacts.

Blake’s contributions – had they come to full fruition – would have been a major contribution to Western knowledge of Chinese plants. Also, by taking Chinese books as references he clearly took Chinese botanical knowledge seriously. His papers allow for a rare insight into the dynamic between Chinese go-betweens and Western botanists in the 18thand even 19thcentury. Indeed, without the help of Chinese translators, gardeners, gatherers and wealthy garden owners, no Western botanist could have undertaken the kind of project that Blake was attempting.

Blake’s project was cut short by his early death in 1773. Around 1775, Whang Ah Tong, a trade intermediary who knew English and who appears to have helped Blake with translations while he was in Canton, returned Blake’s papers and paintings back to his father in England. Some of the drawings were also either acquired by, or given to, Sir Joseph Banks (now in the Natural History Museum, London) and these were used by Banks used to assist the plant collectors he sent to China in the latter part of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Unfortunately, the 19thcentury saw intensified xenophobia and prejudice in Western relations with China, which led them to discount local Chinese knowledge and proved an impediment to more open Sino-Western botanical exchange. Although forgotten after his death, the reappearance of John Bradby Blake’s work in the twenty first century offers a rare glimpse of an earlier more positive dynamic in early Sino-Western cultural and scientific exchanges.