Eline D. Tabak, PhD researcher in English (Bristol) and Environmental Humanities (BSU), introduces her SWW DTP-funded project.

‘According to all known laws of aviation, there is no way a bee should be able to fly. Its wings are too small to get its fat little body off the ground. The bee, of course, flies anyway because bees don’t care what humans think is impossible.’ You might recognise these words as the opening from the animated film Bee Movie (2007). The film is as known for its memes as its compulsive heteronormativity. If you are unaware: not only are there many happy nuclear bee families, the star of the film, Barry, is a male worker bee. On top of that, the human woman with whom Barry takes on the honey industry and fights for equal bee rights appears to develop some warm feelings for him. Needless to say, Bee Movie is fun but not a cinematographic masterpiece.

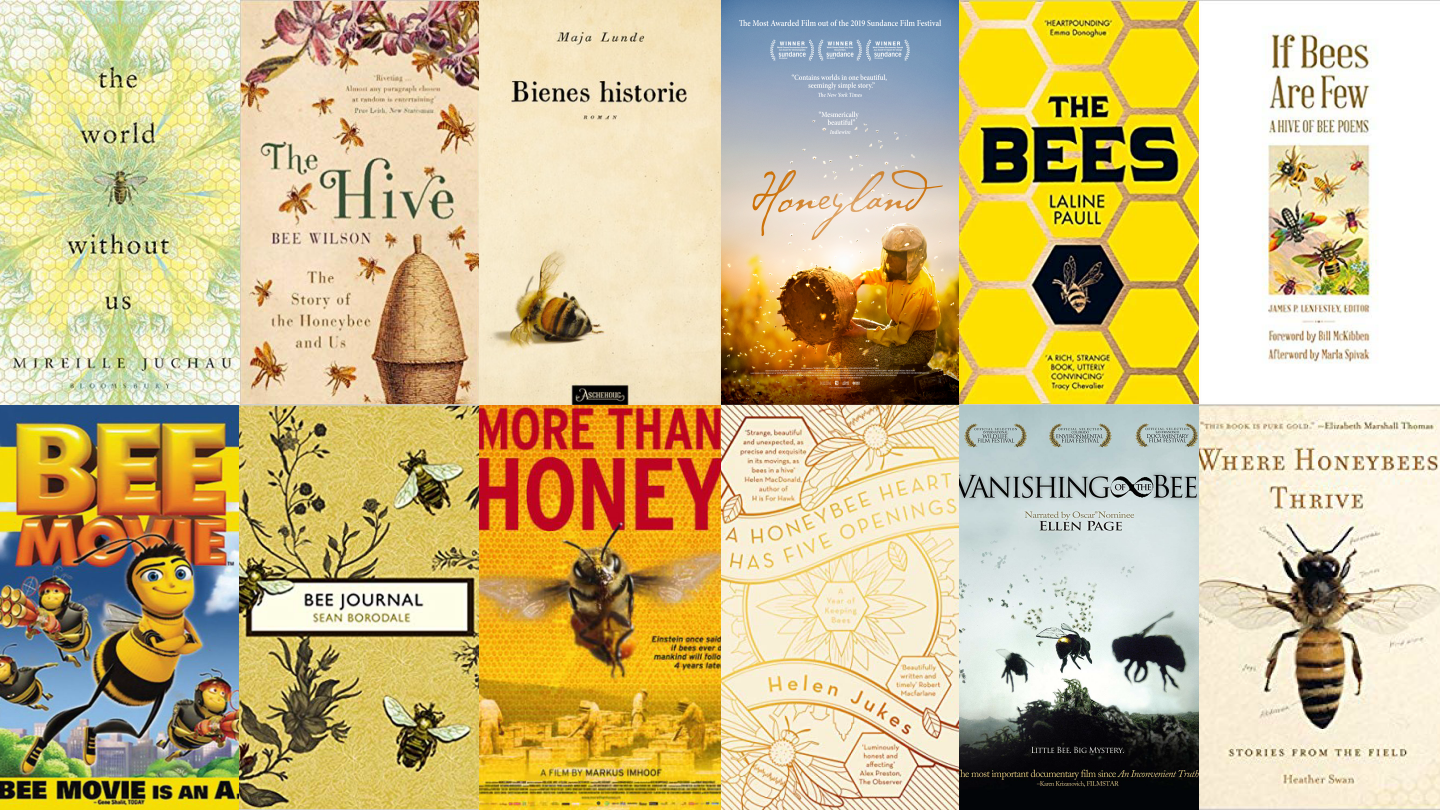

Jokes aside, the 2007 film is a good indicator of an influx of documentaries, memoirs, novels, and poetry collections starring the Western or European honeybee. Perhaps I’m being too critical here. This influx does excite me in a way, as it shows that insect life and decline has become part of a broader conversation. But, with this awareness of insect decline in our cultural imagination comes a sting in the tale. In this case, the sting is an almost obsessive focus on the European honeybee in an age of overall insect decline and what Elizabeth Kolbert (2014) popularised as the sixth extinction. There are thousands of known species of bees all over the world—not to mention other bugs—and yet a select group of people continue to talk, write, film, draw and campaign for the European honeybee. (Are you familiar with the concept of bee-washing?)

In response to these stories, I started thinking about the following: why is there so much creative work on the honeybee? Insects make up the most biodiverse and largest class of described (and estimated) species in the animal kingdom. And while many of these—not all—are indeed facing decline or even extinction, the European honeybee is not one of them.

What started out as a general interest, quickly evolved—metamorphosed!—into my doctoral project on insect decline. Inspired by Ursula Heise’s (2016) work on the cultural side of extinction, I started asking the following: what kind of narratives do people create when talking about insect decline, and how do they tie in with other and older insect stories, our broader cultural memory? Is there an explanation to be found for this honeybee hyperfocus when it comes to narratives of insect decline? Thinking about these questions, I kept returning to Donna Haraway, who wrote that ‘it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with … It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.’ (12) Haraway’s keen (if not overcited) observation also applies to the case of insect decline. When looking at creative storytelling—of which there is a lot—we’re not just considering entertainment or aesthetics. Even with something as seemingly banal as Bee Movie, it does matter what stories we tell to tell the story of insect decline. So why do people contribute to this, for lack of a better word, honeybee extravaganza?

My project become more than a chance to get deep into the problem with honeybees and other charismatic microfauna. Thinking about tiny critters (instead of charismatic megafauna) created the opportunity to engage with and tease out some of the broader questions in the fields of critical animal and extinction studies. Between all the reading and writing and talking and plotting out of the work that needs to be done, theories and ideas and random shower thoughts keep falling into place, and I have a red thread or two running through the different chapters of my thesis. Watch this space.

For now, I do want to say that one of the more rewarding elements of my research so far has been the deep dive into care ethics. My understanding of the concept has both expanded and gained new focus, and my deep dive into care and conservation has opened my eyes to the possibility of care as a violent practice (Salazar Parreñas 2018). One of my current challenges is to see how care, understood as ‘a vital affective state, an ethical obligation and a practical labour’ (Puig de la Bellacasa), is reflected in the poetics of insect decline. What does a poetics of care look like when we let ourselves become subject to, as Haraway (2008) phrased it, the ‘unsettling obligation of curiosity, which requires knowing more at the end of the day than at the beginning’ (36). What happens when we allow ourselves to pay careful attention to the other-than-human life around us and start to care?

Another thread is that of the different (temporal and spatial) scales of extinction and the limits of our empathy for other-than-human animals. As Ursula Heise (2016) and Dolly Jørgensen (2019) so effectively argue in their monographs on the topic, extinctions come to matter once they reflect upon our own (human) pasts, presents, and futures and we can emotionally engage with them. And like these different pasts, presents, and futures, extinction isn’t singular. It is easy—and to a certain extent even useful—to put it all under the label of the sixth extinction. Still, I am increasingly convinced that such labels obscure the differences and intricacies people need to be aware of in the face of the sixth extinction—or rather, extinctions.

There are local extinctions, global extinctions, extinctions completely missed or forgotten (by human eyes), even desired extinctions. Communities respond to and engage with different species and local and global extinctions in different ways. Especially when something tricky like shifting baseline syndrome ensures that some communities aren’t aware of local extinctions or declines in the first place, while passionate campaigns for charismatic megafauna put certain species on the global agenda and in the public eye. I’m not saying this is always a bad thing (I’m just as passionate about the survival of the Malayan and Sumatran tiger as the next person).

I am, however, saying that it is worth researching how attention and care are directed and, ideally, can be redirected in times of need. And insects—in all their creeping and crawling diversity, with important ecosystem functions such as pollination, prey, and waste disposal—have turned out to be an excellent group to consider these questions.

You can follow Eline on twitter @elinetabak and see more of her writing and work at www.elinedtabak.com

Sources

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

—. When Species Meet. U of Minneapolis P, 2008.

Heise, Ursula K. Imagining Extinctions: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. U of Chicago P, 2016.

Jørgensen, Dolly. Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age: Histories of Longing and Belonging. MIT Press, 2019.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. Bloomsbury, 2014.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. U of Minnesota P, 2017. Salazar Parreñas, Juno. Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation. Duke UP, 2018